We need to create a speakers bureau that lists informed patients who are available to participate in conferences and other speaking engagements. I think this idea was first suggested to me by the wonderful Ted Eytan MD. We need infrastructure (a place to host the list) and funding for the speakers.

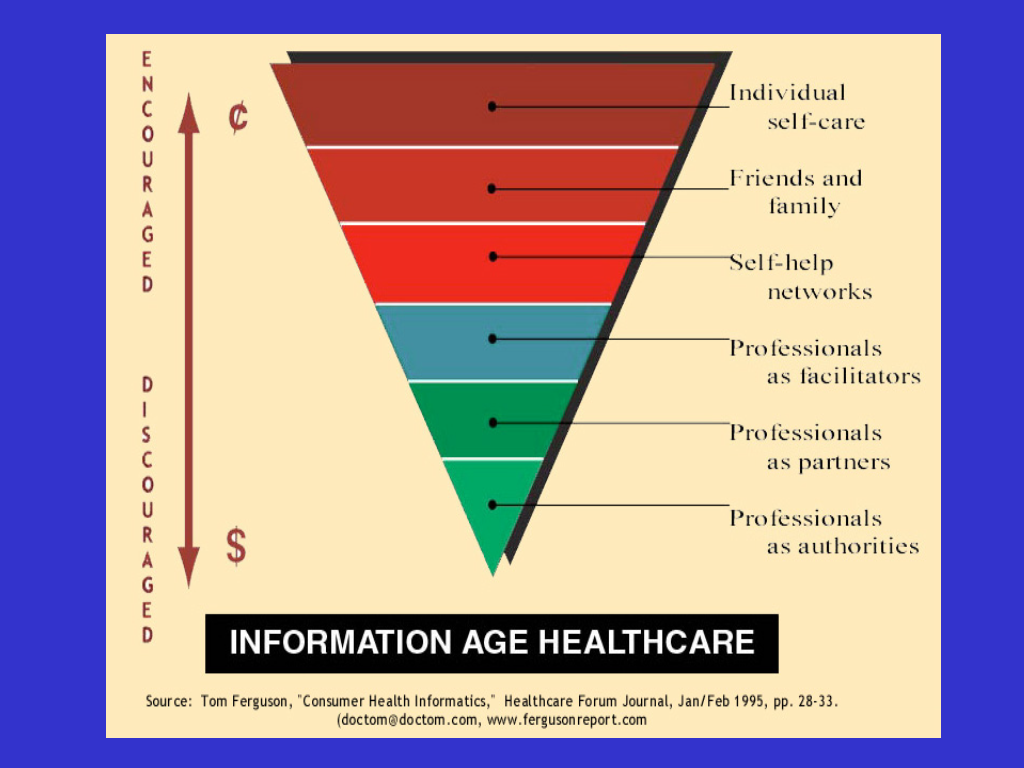

Everyone's talking about creating a new world of healthcare that's more patient-centered or patient-oriented. Actually, in its fullest realization, this will be participatory medicine. (See the many posts on the e-patient blog.)

But how can we do that if patients aren't at the table as this new world is thought out?

There are three separate issues.

- First, conference organizers need to realize that patients should be involved.

- Second, they have to know where to find them. That's where a bureau would come in. (Conference organizers commonly find speakers by turning to a speakers bureau in their field. Google "speakers bureau" and you'll see how widespread they are.)

- Third, patient participation needs to be funded. All other conference participants do it as part of their day job; patients can't.

- I was on a panel at the Mass Tech Leaders healthcare cluster in June, with the CIOs of local hospitals and vendor reps, with investors and analysts in the audience. I had to take time off work.(My parking was validated.)

- That went well enough that I was subsequently invited to be on the Advisory Board for that group. I attended several meetings, and became co-chair of an upcoming event in April. But I had to stop attending meetings because they're workday meetings.

- When I spoke at Connected Health 2008 in October (slides and video), I had to take time off work. It was local for me (Boston), so I only had parking costs ($30). I would have loved to attend both days, talk to people, learn and teach, but I didn't want to use two vacation days.

- Kudos, though, to InvestNI, the Northern Ireland investment group. Northern Ireland is the first country where Europe is rolling out the EU's connected health initiative. They invited me to speak at their dinner that Monday night, and generously gave me a hotel room so I didn't have to drive home to New Hampshire overnight, then back in through morning rush hour.

- I'm speaking (with my doctor) at TEPR+ in Palm Springs on February 1. The conference is paying most of my travel costs, but it's costing me vacation days.